Juan Brignardello Vela

Juan Brignardello, asesor de seguros, se especializa en brindar asesoramiento y gestión comercial en el ámbito de seguros y reclamaciones por siniestros para destacadas empresas en el mercado peruano e internacional.

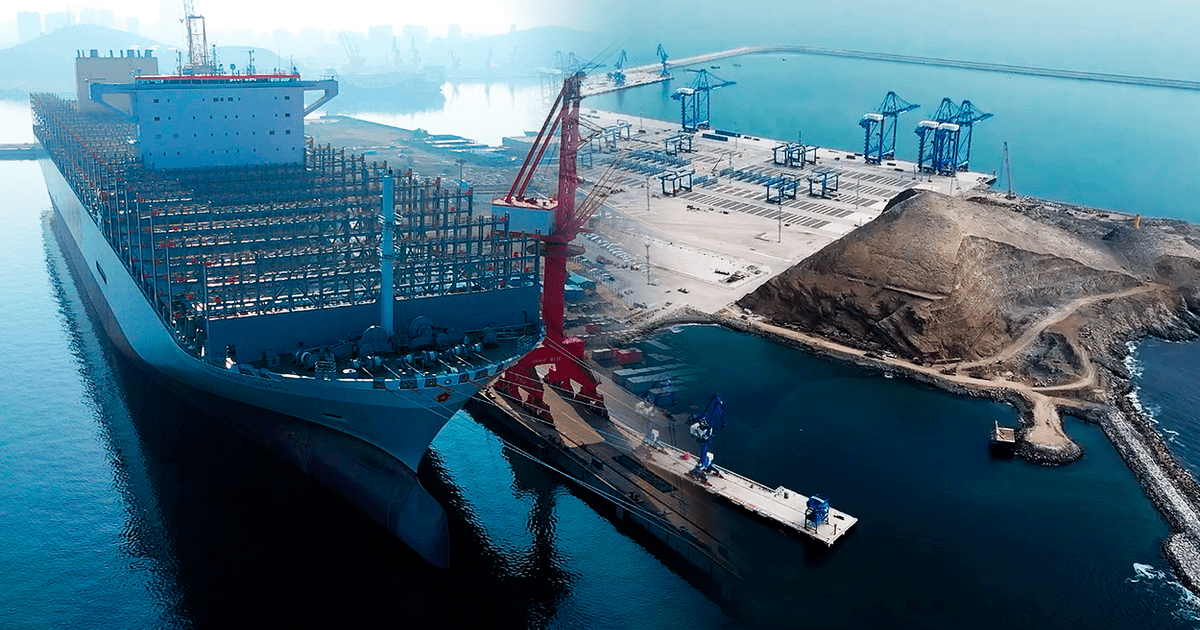

The recent discussion surrounding the inauguration of the Chancay port has brought to light a crucial issue: the creation of a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and the need to consider reduced tax rates as an essential component for its success. However, the debate is not only focused on creating tax incentives but also on the impact these could have on the country's public finances. Over the last five years, tax incentives have exceeded S/ 100 billion, raising serious questions about their effectiveness and sustainability. According to the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), it is estimated that in 2024, nearly S/ 24 billion will not be collected due to exemptions and other tax incentives. This figure represents 2.19% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 14.9% of the expected revenue for the year. The sectors most benefited by these exemptions are agriculture and the Amazon, which together represent a significant cost to the state, highlighting the urgency for a deeper analysis of the nature and effectiveness of these incentives. In the last five years, there has been an 11% increase in tax expenditures, mainly driven by new benefits approved in Congress. This has led the state to forgo approximately S/ 1.4 billion since the implementation of the reduced VAT rate for restaurants and tourism businesses. To put this into context, this amount exceeds the budget allocated to Pension 65 for this year, underscoring the magnitude of the fiscal impact. An alarming aspect of tax incentives is their regressive nature. Often, these fiscal advantages disproportionately benefit larger companies, as seen with the reduced VAT rate, where the top 20% of companies by sales in 2023 concentrated 76% of the benefits. This inequality raises a dilemma about the true mission of these incentives: whether they genuinely seek to promote equitable development or, conversely, perpetuate wealth concentration. History has also shown that many of these incentives tend to perpetuate themselves without solid technical foundations justifying their continuation. A clear example is found in the reimbursement of tariffs, where, despite the MEF seeking to reduce the simplified reimbursement rate, pressure from beneficiaries led to the suspension of this norm. This highlights the lack of adequate control and the influence that interest groups can exert over tax policy. Moreover, it has been evidenced that exemptions, in some cases, have favored illegal economies, such as informal mining in the Amazon. Here, fuel consumption, exempt from VAT and ISC, has grown at an alarming rate, suggesting that these policies are not only costly but also lack the necessary controls to ensure they benefit the sectors that truly need them. International organizations, such as the IMF and the OECD, have emphasized that for companies with global investments, certainty in the tax system is more important than the existence of tax incentives. This perspective challenges the common notion that more incentives lead to greater economic development. On the contrary, it has been recorded that these incentives often fail to meet their objectives, suggesting that tax policy needs to be reconsidered. The proposal for an SEZ in Chancay should go beyond simply offering reduced tax rates. Instead, a comprehensive approach is needed that considers investment requirements, substantial activities in the zone, adequate infrastructure development, and a commitment to workforce training. Without this strategy, any attempt to attract investment may result in a trap that benefits the capital's country of origin more than the local economy. The experience of the San Martín region, which has opted for a different approach by partially renouncing tax exemptions in favor of a trust for infrastructure projects, shows that it is possible to achieve more sustainable economic growth and effective poverty reduction without relying on tax incentives. This alternative should serve as a model for restructuring public policies in other regions of the country. Finally, in the current context of fiscal crisis, where a deficit of 3.6% of GDP is projected for 2024, it is imperative to review existing tax incentives and halt the implementation of new ones. The lack of control and oversight, along with the growing inequality in the distribution of benefits, presents a scenario that requires urgent attention. The discussion about the Chancay SEZ should be an opportunity to rethink the country's tax strategy and ensure a more efficient use of public resources.